Eritrea

di Maurizio Frullani

Leafing through the pages of Maurizio Frullani’s book the sensation prevails that the images come from a vision that goes beyond photography, which is used more as a tool for research.

It is certainly not simple to approach and understand lands in other latitudes, but Frullani is first and foremost a traveller then a photographer, and this gives important added value to his work.

The traveller is above all one who has no prejudices and is willing to discover and understand even what is outside known coordinates, accepting what is different from us.

During her Grand Tour in Italy, George Sand wrote “…Never read my letters in the hope of discovering minute details about exterior objects; I see everything through personal impressions. A journey is for me nothing more than a course in psychology in which I am the subject who submits to all the tests and experiences that tempt me …”

Over the years Frullani’s profound traveller’s soul has led him into the Middle and Far East which he reached by land where possible and then by air due to the wars that have devastated those regions. He writes of this experience “Time stopped, or rather turned back, arousing in the heart and bringing again to mind sweet childhood insights, visions of a thousand and one nights, landscapes, situations and real and imaginary characters”. Certainly these evocations do not lack the burning ember that accompanied him in his important project “Saints, Myths and Legends” where mythical visions and very human emotions merge.

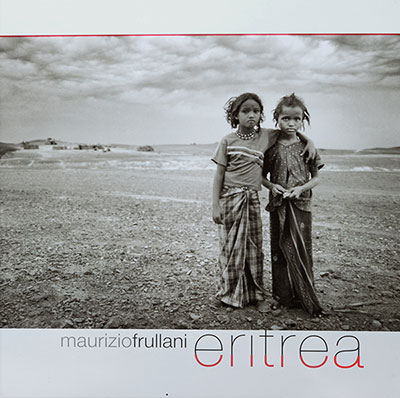

But perhaps of all the places he has seen, the continent he has under his skin is the fascinating ancestral land of Africa. And so here is Eritrea, a publication that collects some of the many images Frullani produced during a seven year sojourn: a narrative about people, environments and relationships, told by intense portraits of this African nation.

Homes, courtyards and workshops are environments that help to weave a tale in which women, children, elders and artisans appear naturally to show their lives and themselves with simplicity.

They do not seem to experience the objective as an intruder, but as something that can be trusted because the photographer has the skill to represent their community, respecting their life’s pace and the time it takes to enter into a relationship with a foreigner.

In this way we discover ancient gestures and archaic tasks, but also deep family relationships and simple children’s games: Frullani’s photographs make the ordinary extraordinary.

This is possible because of his attention to form which, contrary to expectations, does not make images cold and edulcorated but broadens their sense, making their message purer. It is the purity we perceive when we encounter soulful eyes, shadows of smiles, small plaits, loose or tied up in colourful headscarves, clothes we see as highly coloured in spite of black and white: these are the beautiful Eritrean women who are not camera shy and face the lens with the firm gaze of those who are aware they are expressing their dignity.

A dignity that Frullani’s photographs render intensely and which takes on greater value when we consider the difficulties that these and other African women have encountered as mothers, wives and daughters throughout the history of their countries. The hard living conditions weigh mostly on the women, who have been subjected to abuse and bodily violence that ancestral traditions imposed, and in some places still impose.

When photography triggers a thought that makes us reflect it means that the author has been successful in capturing the deep relationship that exists between places, history and life, without falling into the trap of rhetoric or folklore.

We should be grateful for this to Maurizio Frullani’s observant eye, the eye of a traveller who becomes a photographer.